2014 Abstracts

Speaker Abstracts

Nicole Aljoe

This talk will discuss a few salient points about the history of Black people in Britain in the 18th century. In addition to the lives of “celebrities” like Olaudah Equiano, Ignatius Sancho, and Dido Belle (the last a retroactive celeb), we will also consider stories about the lives of “ordinary” Black British peoples that are now being re-discovered. And because many if not most Blacks in England at this time were enslaved, we will also consider the ways in which writing and reading slave narratives operated as a kind of portraiture – offering readers pictures of life under enslavement.

Nicholas Draper

“Legacies of British Slave-ownership: making the archive public”

When Britain ended chattel slavery in its colonies in the 1830s, it paid �20MM in compensation to the slave-owners: the enslaved people themselves received nothing. This paper examines the unique census of British colonial slave-ownership created by the distribution of this compensation to 47,000 individual slave-owners throughout the Empire, in order to highlight areas of silence and elision in the archive, raise issues involved in recovering the histories of enslavers rather than those of enslaved people, and discuss the implications of making this material fully available as a public resource.

Saidiya Hartman

“Archival Fictions”

My remarks explore the intimacy of fact and imagination in the engagement with the archive of slavery. On one hand, history as a disciplinary practice demands fidelity to the archive and submission to its governance of the possible; on the other, artists and writers have produced many of the most compelling accounts of slavery as an institution of power and have rendered the lives of the enslaved in richly complex terms that trouble the categories of subject and object, past and present, and life and death by imagining other archives, by disfiguring and remaking the archive, and by exploring other protocols for reading. This traffic between fact and imagination has been incredibly productive and has prodded scholars to consider the investments and consequences of our disciplinary practice.

Agnes Lugo-Ortiz

“On the Appearance of the Enslaved’s Face in Visual Portraiture”

Despite their historically parallel development, in conceptual terms, modern plantation slavery and the pictorial genre of “portraiture” could not appear to be more mutually exclusive and radically divergent. The logic of chattel slavery sought to render enslaved beings as instruments for production, as sites of non-subjectivity, as entities that were more “body” than “face.” Portraiture, on the contrary, privileged the face as the primary visual matrix for the representation of a distinct individuality. How does one account, then, for the seemingly paradoxical existence in the history of the Atlantic world of objects that demand to be perceived as “portraits of slaves?” In this talk I will unpack the apparent conceptual dissonances between “enslavement” and “portrait” and will lay out some of the conditions that made the appearance of the slave’s face historically possible in the dignifying realm of visual portraiture.

Wayne Modest

“Remembering to Forget: Ignorance and the curating of slavery”

In this brief presentation, I will explore the ways in which slavery was recently represented in museums in Amsterdam, locating them within a broader context of what I have called an anxious politics of the present surrounding questions of citizenship and belonging in contemporary Europe. I will also draw some comparison to the bicentenary celebrations of the abolition of slavery that took place in Britain in 2007 showing some of the differences and similarities between these different acts of museal commemoration.

2013 marked the 150th anniversary of the emancipation of the enslaved in the Dutch Kingdom. To mark this anniversary four Dutch museums located in Amsterdam curated exhibitions exploring both the history of the slavery past as well as the legacy of slavery within contemporary Dutch society. Importantly, these exhibitions coincided with significant budget cuts within the cultural sector, resulting from austerity measures, that saw several “postcolonial” museums/cultural institutions being closed. But what does this “high volume” of exhibitions within these major Dutch museums say about the memory of slavery in present day Dutch society and about the representation of slavery within the public sphere? And how might we understand this attention to slavery in museums on the one hand and the closure of institutions dedicated to telling the story of postcolonial Netherlands on the other? The presentation will also extend some work that I have been doing recently on Ignorance as a theoretical framework for thinking about histories in the present.

Catherine A. Molineux

“Faces of Perfect Ebony”

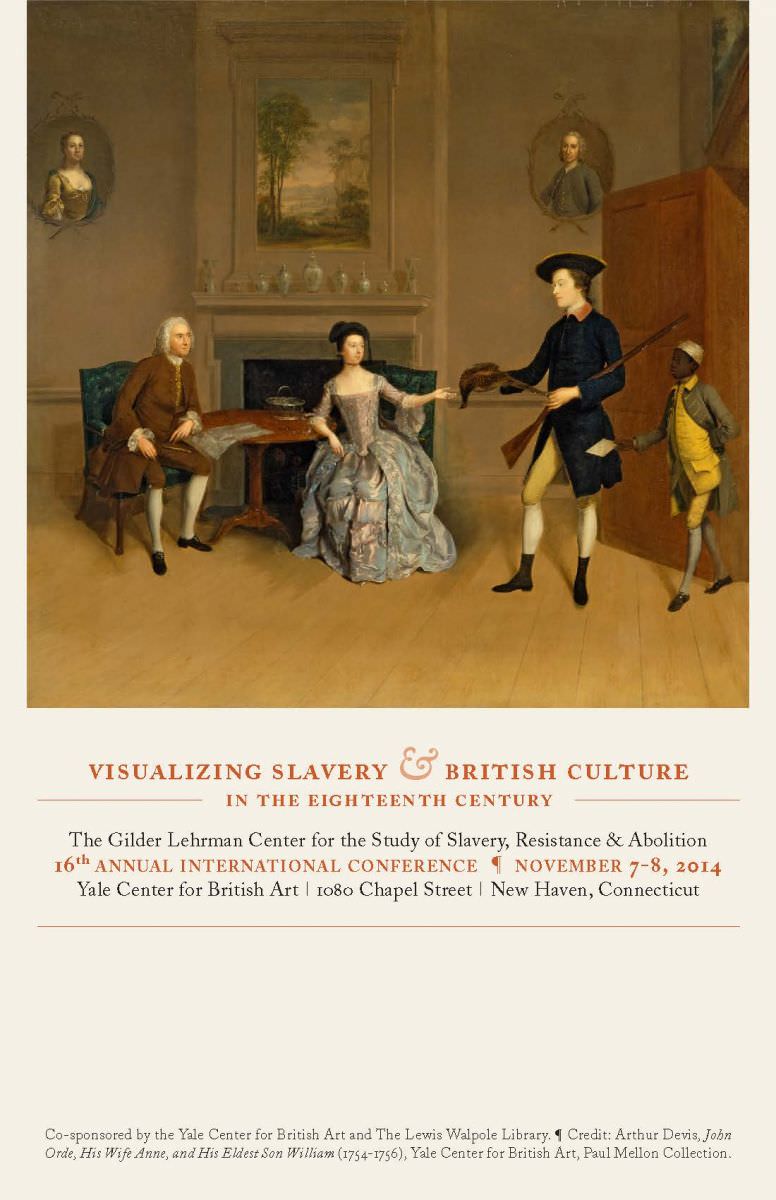

My talk situates the objects in the YCBA exhibition in the broader visual and material landscape of slavery in seventeenth and eighteenth-century Britain. By tracing, in brief, the development of British aesthetic responses to rise of the British slave trade, these various objects capture, on the one hand, a persistent idealism about the significance of new interracial relationships and, on the other, an increasingly vocal critique of British involvement in the trade. My talk, which draws on my book Faces of Perfect Ebony, will highlight how this aesthetic engagement reflected Britain�s unique place within the early modern Atlantic world.

Steven Pincus

In my brief talk I will discuss Eli Yale and slavery. The central methodological claim of my paper is that because chattel slavery in the New World was shaped by political and institutional rather than narrowly social and economic forces, any account of slave portraiture needs to move beyond the techniques of social and cultural history (the techniques espouse by the now dated but still fashionable “new imperial history”) and include those of political history and the new history of institutions.

Geoff Quilley

“Nelson in a bottle in Trafalgar Square: placing slavery and circum-Atlantic memory”

My “conversation” will take as a springboard Yinka Shonibare’s recent sculpture Nelson’s Ship in a Bottle (2010), first displayed on the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square, London, and now permanently housed at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich. I will use this to question how slavery and its histories are “placed,” “misplaced” or “displaced” within (visual) cultural history in Britain and the wider circum-Atlantic world. I am particularly interested here in how artists such as Shonibare respond to and utlilize eighteenth-century visual precedents for particular, counter-narrative ends in their work; and how this in turn corresponds to Ian Baucom’s idea of the “inordinately long” twentieth century, as both a collapsing and also a spatializing of historical chronology, linking the eighteenth and the twenty-first centuries across a circum-Atlantic cultural economy. Thinking about Shonibare’s sculpture as an autographed work, an assertion of subjectivity, and in part a form of self-portrait, will also be important here.

Richard Rabinowitz

“Risky Crossings: The History Curator in the Art Museum”

In my brief talk, I will contrast the way art and history museums present the history of slavery, exploring differing approaches to the displayed objects, pedagogy, and the design of the visitors’ experience.

Joseph Roach

I will be talking about the (fictional?) slave narratives performed daily in the repertoire of London, provincial, and colonial stages, centered on Thomas Southerne’s adaptation of Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko; or, The Royal Slave, the most popular tragedy of the 18th century English stage after Shakespeare. The theme I want to pick up on is how the directly represented violence of the stage returns like the repressed in the conversation pieces in Figures of Empire.

Edward Rugemer

“London’s Black Community, the Somerset Case, and the Politics of Slavery”

James Walvin

“Slavery in Small Things”

The richness and ubiquity of evidence about slavery is confirmed by the continuing outpouring of scholarship on the subject. The richly-layered documentation about slavery may seem most obvious and abundant in the American locations which became home to different forms of slavery. Yet some of the most obvious, visible and commonplace of materials lie in Europe, and is sometimes overlooked by historians. Or more precisely, such material is not always situated in its enslaved context. In part, this is because, when viewed from London or Paris, slavery may seem out of sight and therefore out of mind. This paper, a précis of a book on the same subject, will discuss how certain commonplace artefacts – all of them familiar in modern western life – offer an entrée the history of slavery.

Galleries, museums and private collections are filled with material artefacts which derive directly from slavery. A few examples will suffice: the Sevres sugar bowl sold at Christies in 2010 for �18,750 (about $30,000), the sumptuous painting of Belle which inspired the recent (and highly fictionalised) movie, Chippendale’s gleaming mahogany furniture which graces the State Dining Room in Harewood House In Yorkshire, simple cowrie shells used as items of personal decoration the world over. Such objects point not merely to the history of Atlantic slavery but also illustrate one of slavery’s great paradoxes. Here was a brutal and exploitative system which generated not merely the wealth we are all familiar with, but made possible new forms of western refinement, fashionable taste and sophistication. But who, when looking at some of the most exquisite features of late 18th century material culture and fashion, makes the connection with human bondage?

Roxann Wheeler

“A Colloquial Archive of Color-Conscious Insult and Slang in Eighteenth-Century Britain”

This artificial archive draws together color-conscious insult and slang from multiple sources in order to bring to the foreground black and brown servants, laborers, and slaves, all regrettably obscure historical and fictional figures. The collection of printed colloquial speech – who said what to whom, when, and in what context – is recovered from journals, letters, newspapers, histories of the colonies, dictionaries, popular songs, stage plays, and novels published between 1650 and 1808, and it also includes a few words of West Indian slave dialect that filtered into popular British culture. I analyze the tonal range and typicality of color-conscious demotic terms to lend some much needed dimensionality to our perception both of color prejudice and intimacy. Intriguingly, some special slang terms such as lilywhite and snowball and even commonplace slang, such as blacky, comprehended chimney sweeps, colliers, blacksmiths, and people of African descent.

Chi-ming Yang

“Bodies Like Lacquer”

From blackamoor statuary to japanned screens and folding fans, finely wrought decorative art furnished the eighteenth-century culture of slavery in England. As components of sumptuous interiors, Asian objects created new tastes for the exotic even as they romanticized and color-coded the laboring bodies of East and West Indian slaves. Through considering chinoiserie design and the marvelous surface sheen of lacquer and porcelain wares, this talk will highlight the aesthetics of racialized labor and the ethics of luxury consumption in a transpacific as well as transatlantic frame.