Yale vows new actions to address past ties to slavery, issues apology, book

Yale today announced further actions to address findings from the Yale and Slavery Research Project, published a book about the findings, and issued an apology.

Yale University’s ongoing work to understand its history and connections to slavery continued today with announcements of new commitments and actions and a formal apology in response to the findings of a scholarly, peer-reviewed book, “Yale and Slavery: A History,” authored by Yale Professor David W. Blight with the Yale and Slavery Research Project.

“Confronting this history helps us to build a stronger community and realize our aspirations to create a better future,” Peter Salovey, Yale’s president, and Josh Bekenstein, senior trustee of the Yale Corporation, wrote in a message to the university community. “Today, on behalf of Yale University, we recognize our university’s historical role in and associations with slavery, as well as the labor, the experiences, and the contributions of enslaved people to our university’s history, and we apologize for the ways that Yale’s leaders, over the course of our early history, participated in slavery.

The findings

Through its research, the Yale and Slavery Research Project “has deepened greatly our understanding of our university’s history with slavery and the role of enslaved individuals who participated in the construction of a Yale building or whose labor enriched prominent leaders who made gifts to Yale,” Salovey and Bekenstein said.

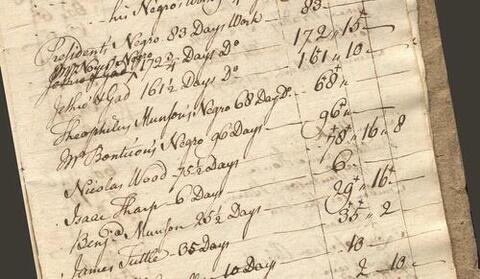

Although there are no known records of Yale University owning enslaved people, many of Yale’s Puritan founders owned enslaved people, as did a significant number of Yale’s early leaders and other prominent members of the university community. The research project has identified over 200 of these enslaved people, the message said. The majority of those who were enslaved are identified as Black, but some are identified as Indigenous. Some of those enslaved participated in the construction of Connecticut Hall, the oldest building on campus. Others worked in cotton fields, rum refineries, and other punishing places in Connecticut or elsewhere.

“Their grueling labor benefited those who contributed funds to Yale,” the message said.

The project’s findings also revealed that prominent members of the Yale community joined with New Haven leaders and citizens to stop a proposal to build a college in New Haven for Black youth in 1831, which would have been America’s first Black college.

Additional aspects of Yale’s history are illuminated in the book’s findings, including the Yale Civil War Memorial that honors those who fought for the North and the South without any mention of slavery or other context, the message said.

Many of the project’s findings have been shared publicly and addressed by Yale on an ongoing basis during the research process.

‘Our forward-looking commitment’

Based on the Yale and Slavery Research Project’s findings and the university’s history, Yale leaders announced new actions that focus “on systemic issues that echo in our nation’s legacy of slavery.”

The actions focus on increasing educational access; advancing inclusive economic growth; better reflecting history across campus; and creating wide access to Yale’s historical findings. The Yale and Slavery Research Project is part of Yale’s broader Belonging work to enhance diversity, support equity, and promote an environment of welcome, inclusion, and respect.

“The new work we undertake advances inclusive economic growth in New Haven,” Salovey and Bekenstein said. “Aligned with our core educational mission, we also are ensuring that our history, in its entirety, is better reflected across campus, and we are creating widespread access to Yale’s historical findings.”

The full details of the university’s response are available on the Yale and Slavery Reseearch Project website.

Several of the university’s commitments are highlighted below:

‘Increasing educational access and excellence in teaching and research’

The lost opportunity to build a college for Black students in New Haven in 1831 has prompted Yale to strengthen its partnerships with the nation’s Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) and to expand educational pathways for New Haven youth.

- New Haven School Teachers: New Haven, as well as the rest of the country, is dealing with an acute and ongoing teacher shortage; in the city, there were 80 teaching positions that went unfilled during the last academic year. There are many reasons for this shortage, including the high costs of acquiring certification and a master’s in teaching degree, compared to the relatively modest compensation in the profession. “We are partnering with the New Haven Public School system, New Haven Promise, and Southern Connecticut State University to design a new residency fellowship program to provide funding to aspiring teachers, so they can attain a Master’s in Teaching degree in exchange for a commitment of at least three years of service in the New Haven Public School system,” Salovey and Bekenstein said. Once launched, this fellowship program aims to place 100 teachers with master’s degrees into the city’s schools in five years.

- Yale and Slavery Teachers Institute Program: Yale will also launch a four-year teacher’s institute in summer 2025 to foster innovation in the ways regional history is taught. This program will help K-12 teachers in New England meet new state mandates for incorporating Black and Indigenous history into their curricula. Each year, a cohort of teachers will engage with partners within and outside of the university community to study content and methods related to a particular theme, using the book “Yale and Slavery: A History” as “a springboard.” The first year of the program will focus on Indigenous history, followed by slavery in the north, and Reconstruction and the Black freedom struggle. Led by the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition at the Yale MacMillan Center, the program will provide a platform for teachers in New England to co-develop curricular materials, in collaboration with scholars, public historians, Native communities, and other groups. The pedagogical materials and methods created through the program will be disseminated broadly for the benefit of students, educators, and the general public throughout the region.

- HBCU Research Partnerships: Yale continues to expand its research partnerships with HBCUs across the country with pathways programs for students, opportunities for faculty collaboration, and faculty exchange programs. The university will announce a significant new investment in the coming weeks.

- New Haven Promise Program: In January 2022, Yale expanded its contribution to New Haven Promise, a college scholarship and career development program that has supported more than 2,800 students from the New Haven Public Schools, by 25% annually, from $4 million to $5 million, and extended its commitment through June 2026.

- Pennington Fellowships: In December 2022, Yale launched a new scholarship to support New Haven high school graduates to attend one of its partner HBCU institutions (Hampton University, Howard University, Morehouse College, Morgan State University, North Carolina A&T, and Spelman College). The program is designed to help address historical disparities in educational opportunities for students from New Haven and will grow to include 40 to 50 Pennington scholars at any given time, supporting students in their academic, financial, and career entry success.

- Law School Access Program: Yale Law School’s pipeline program serves first-generation, low-income, and under-represented students from New Haven. The program invests in a class of up to 20 fellows who are “passionate about uplifting their local communities” in New Haven and Connecticut. Yale began centrally co-funding the program with the law school in 2024 to ensure its long-term stability.

- K-12 Educational Outreach in New Haven: Yale supports many programs for youth in New Haven and surrounding communities, and thousands of public school children take part in Yale-funded academic and social development programs. These include Yale’s Pathways to Science and Yale’s Pathways to Arts and Humanities programs.

‘Advancing inclusive economic growth in New Haven’

Yale remains committed to partnering with the City of New Haven to create vibrant shared communities with increased economic opportunities. This builds on the university’s ongoing work with the New Haven community, which includes increasing what was already the largest voluntary payment by a university to its host city in the country to approximately $135 million over six years and the creation of a new Center for Inclusive Growth to develop and implement strategies to grow the city economically.

- Dixwell Plaza: Yale recently signed a 10-year letter of intent for space at Dixwell Plaza to support the development of a state-of-the-art mixed-use retail, residential, and cultural hub in Dixwell’s historically Black community center that is rooted in restorative economic development. Yale is working on this initiative with the Connecticut Community Outreach and Revitalization Program (ConnCORP), a local organization whose mission is to provide opportunities to New Haven’s underserved residents.

- Community Investment Program: Yale’s community investment program works with independently owned retail businesses. Most recently, University Properties has supported a growing number of locally owned brick-and-mortar businesses, including restaurants and retail clothing stores. This program brings jobs to New Haven residents and expands the city’s tax base.

‘Acknowledging our past’

The Yale and Slavery Research Project’s findings make clear that Yale’s foundations are inextricably bound with the economic and political systems of slavery, Salovey and Bekenstein wrote in the message. “That history is not fully evident on our campus, and we are working to ensure that our physical campus provides members of our community with a more complete view of the university’s history,” they said, noting the following projects:

- Transforming Connecticut Hall: Connecticut Hall, constructed in the mid-18th century using in part the labor of enslaved people, is being reconstituted as a place of healing and communion as the new home of the Yale Chaplaincy. The Yale Committee on Art Representing Enslavement will make recommendations for how the building’s history with slavery can be acknowledged and made evident through art. The renovated building is currently slated to be reopened in summer 2025.

- Civil War Memorial: Yale’s Civil War Memorial, located in Memorial Hall and dedicated in 1915, is a “Lost Cause” monument. However, the purpose and meaning of the memorial are largely unknown to most people who walk past it. Recently, an educational display was installed near the memorial to educate visitors on its history and provide additional resources.

- Committee for Art Recognizing Enslavement: In June 2023, the university launched the Yale Committee for Art Recognizing Enslavement, which includes representatives from both the Yale and New Haven communities. The committee is working with (and soliciting input from) members of the campus and New Haven communities to commission works of art and related programming to address Yale’s historical roles and associations with slavery and the slave trade, as well as the legacy of that history.

- M.A. Privatim degrees: In April 2023, the Yale board of trustees voted to confer M.A. Privatim degrees on the Rev. James W. C. Pennington (c. 1807-1870) and the Rev. Alexander Crummell (1819-1898). Both men studied theology at Yale, but because they were Black, the university did not allow them to register formally for classes or matriculate for a degree. On Sept. 14, 2023, the university held a ceremony to honor the two men and commemorate the conferral of the degrees.

‘Creating widespread access to historical findings’

The book “Yale and Slavery: A History” provides a more complete narrative of Yale’s history — as well as that of New Haven, Connecticut, and the nation. Aligned with the university’s core educational mission, Yale will provide opportunities for communities within and beyond Yale’s campus to learn from the findings.

- New Haven Museum Exhibition: Today, Yale opened a new exhibition at the New Haven Museum, created in collaboration with the Yale University Library, the Yale and Slavery Research Project, and the museum. On view through the summer, the exhibition complements the publication of “Yale and Slavery: A History” and draws from the research project’s key findings in areas such as the economy and trade, Black churches and schools, the 1831 Black college proposal, and memory and memorialization in the 20th century and today. The exhibition places a special focus on stories of Black New Haven, including early Black students and alumni of Yale, from the 1830s to 1940. There is no admission fee for viewing the exhibition.

- Book Distribution: Yale will provide copies of the book to each public library and high school in New Haven, as well as to local churches and other community organizations. The university has subsidized a free e-book version that is available to everyone.

- DeVane Lecture in Fall 2024: Blight will teach the next DeVane Lecture — a semester-long lecture series open to the public — during the Fall 2024 semester. Students can take the course for credit, and the lectures are free to attend for New Haven and other local community members. His course will cover the findings of the Yale and Slavery Research Project and related scholarly work. The lectures will be filmed and made available for free online in 2025.

- App-Guided Tour: A new app includes a map of key sites on campus and in New Haven with narration, offering users the opportunity to take a self-guided tour. The tour’s 16 stops start with the John Pierpont House on Elm Street and end at Eli Whitney’s tomb in the Grove Street Cemetery.

- Campus Tours: With a more accurate understanding of Yale’s history, the university is updating campus tours so that they include the key findings from the Yale and Slavery Research Project, particularly concerning the Civil War Memorial and Connecticut Hall.

Working together to strengthen the community

The university’s commitments are ongoing, “and there remains more to be accomplished in the years ahead,” Salovey and Bekenstein said.

Yale has established a Committee on Addressing the Legacy of Slavery to seek broad input from faculty, students, staff, alumni, New Haven community members, and external experts and leaders on actions Yale can take to address its history and legacy of slavery and “create a stronger and more inclusive university community that pursues research, teaching, scholarship, practice, and preservation of the highest caliber,” they said. The committee will be chaired by Secretary and Vice President for University Life Kimberly Goff-Crews.

Salovey and Bekenstein also invited members of the Yale and New Haven communities to read the book and share their comments. The Committee on Addressing the Legacy of Slavery will review all input and consider future opportunities — with New Haven, other universities, and other communities — to improve access to education and enhance inclusive economic growth, they said. The committee will report to the president.

In the coming weeks, the committee will host listening sessions for faculty, students, staff, and alumni. The Committee for Art Recognizing Enslavement will also host forums for members of the community.

In their message, Salovey and Bekenstein noted that the Yale and Slavery Research Project “has helped gain a more complete understanding of our university’s history.” They said the steps and initiatives Yale has established in response to the historical findings build on the university’s continued commitments to the New Haven community and its ongoing Belonging at Yale work to enhance diversity, support equity, and promote an environment of welcome, inclusion, and respect.

Several community and higher education leaders shared their thoughts about Yale’s announcement and plans.

“I applaud Yale for studying its history more fully and responding to its historical ties to slavery by building on the partnerships it has with the New Haven community,” said Madeline Negrόn, superintendent of the New Haven Public Schools. “I welcome the possibility of Yale supporting the Teacher Residency Program for New Haven. Teacher recruitment and retention is one of New Haven Public Schools’ priorities.

“We are eager to partner with Yale to finalize the design and implementation of a fellowship program aimed to support developing high quality and diverse teachers to stay long term in New Haven Public Schools.”

Yale’s police chief, Anthony Campbell, said:

“Yale University’s leadership acknowledges the institution’s role in the travesty of slavery in the United States, recognizing that as a place of higher learning and research, it must confront and acknowledge this history. While Yale itself did not own slaves, the acknowledgment that some of its founders were slaveholders and that the oldest building on campus was constructed with slave labor underscores the university’s commitment to transparency and healing.

“Furthermore, Yale’s support for the New Haven community, evidenced by its partnership with the New Haven Promise Program and the establishment of the Reverend Pennington Scholarships, signifies its dedication to the healing process.”

Lt. Gen. (Ret.) Darrell K. Williams, the 13th president of Hampton University, said:

“Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was correct — the moral arc of the universe is long, but it bends toward justice. I also firmly believe that truth is essential to justice, and thus, with more truth comes more justice. I applaud the Yale community’s courage to publicly acknowledge Yale’s role in such a painful and consequential chapter of America’s story.”

In their message to the Yale community, Salovey and Bekenstein wrote:

“Today, we mark one milestone in our journey to creating a stronger and more inclusive Yale and to confronting deeply rooted challenges in society to do our part in building ‘the beloved community’ envisioned by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

“Our work continues, and we welcome your thoughts and hope you will engage with our history.”