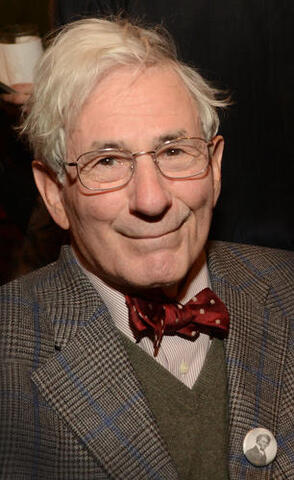

Richard Gilder, Jr., 1932-2020

On May 12, 2020, Richard Gilder, Jr. died. Above all Dick was a great New Yorker, an extraordinary and generous Yale University graduate, class of 1954, and a visionary citizen and lover of the history of his country, its flaws and its triumphs. He died just shy of his 88th birthday. He and his wife, Lois Chiles, had been living in recent months in Charlottesville, Virginia. According to a friend, Dick enjoyed a good final day: he played a board game with a friend, smoked two cigars, had a good scotch, and passed peacefully with no pain.

At the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition at the MacMillan Center at Yale, we mourn our founder who, along with his dear friend in philanthropy and partner in their love of history, Lewis Lehrman, and in close association with the late David Brion Davis, the world’s leading historian of slavery, created this unique institute in 1998. Dick’s generosity has in great part sustained the Center for nearly twenty-two years. Thousands of people have attended our conferences, hundreds have held our fellowships, countless teachers have participated in our seminars, and dozens of scholars have engaged with or, indeed, won our Frederick Douglass Book Prize, which Dick and Lew created.

In 1968 Dick founded the brokerage firm, Gilder, Gagnon, Howe & Co. in New York. As late as four years ago he still worked from a desk among colleagues in the middle of that firm’s traders and investors. For many years we met for the jury’s final deliberations to determine each year’s winner of the Frederick Douglass Book Prize in the seminar room of the firm, overlooking Central Park to the north, in mid-town Manhattan. Dick attended those gatherings and in the early years of my tenure as director of the GLC he would very much weigh in with his thoughts on each book. The scholars and writers around that table, I think, relished the sense of a businessman’s deep admiration and grasp of our craft. Those were rare moments of empathy and understanding in the lives of literary and academic professionals joining in appreciation of the love of books with a titan of the stock market, a world most of us never saw.

At Yale, Dick’s mark of generosity is almost immeasurable, from the rowing teams’ boat house, to the drama school, to science programs, to the class of 1954 endowed chairs, to the beloved and beautiful nave of Sterling Library. Dick’s impact with philanthropy has left indelible marks beyond Yale, as well. The Gilder Lehrman Institute for American History (the most ambitious and successful private philanthropic support for the teaching of history in the United States), the Central Park Conservancy, the New York Historical Society, the Museum of Natural History, and numerous other institutions in New York and in the wider world have benefitted from Dick’s curiosity, passion, and sheer joy in civic commitment. In his support for the study of slavery, its abolition, and its legacies across time and all borders Dick never blinked in his openness to understanding this terrible but so instructive story about human nature and human affairs. He wanted Americans and people everywhere to face the past however it shapes us. He put his confidence and his resources behind the effort to create knowledge about human exploitation and to spread that knowledge around the world. He trusted historians, expertise, research, and the great arts of teaching. He set in motion an institutional means by which to cross all manner of political, economic, racial, and ethnic boundaries in grasping the meaning of the past. He was a history major at Yale.

As long as our Center exists, we will remember and honor Dick Gilder’s commitment to us and repay it with our devotion to our craft, to our colleagues across the globe, to our students, and to the public education he has helped us foster. Much more can and will be said about Dick’s legacy around Yale and beyond. For now, we wanted everyone in our GLC network to know of Dick’s passing and something of why it matters.

In 1884 Frederick Douglass wrote this reflection on why the past and our memory matters. “Memory,” said the aging abolitionist, “was given to man for some wise purpose. The past is… the mirror in which we may discern the dim outlines of the future and by which we may make them more symmetrical.” Such may be to some extent how Dick Gilder envisioned the uses of the past in his grand, public-spirited ways. We may never make the past symmetrical. But especially in times as trying as our own historical moment, we need to lovingly remember and take inspiration from those who help us make a future.

David W. Blight

Sterling Professor of American History, Director, the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition, at the MacMillan Center at Yale University

Photographs from the 2013 Frederick Douglass Book Prize ceremony