Book discussion on human rights activist Arthur Ashe

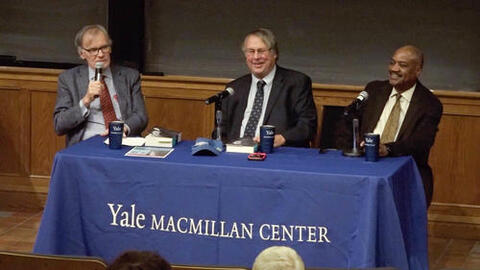

On October 22, the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Abolition, and Resistance (GLC) at the MacMillan Center hosted a book talk with Raymond O. Arsenault, the John Hope Franklin Professor of Southern History and co-director of the Florida Studies Program at the University of South Florida, St. Petersburg. Professor Arsenault was in conversation with Benny Sims Jr., the first African American assistant tennis coach in the Ivy League (Harvard) and the first African American to be named head tennis pro at the famed Longwood Cricket Club, about Arsenault’s latest book, a biography of Arthur Ashe: A Life. (View Discussion)

Yale students, New Haven public school students, educators, and community members came together to get an inside look at one of the most influential athletes and Civil Rights activists—Arthur Ashe. Across three microphones, piles of books, and pages of notes of stories they both spoke about their relationship with Ashe. David Blight, director of the GLC and Sterling Professor of American History at Yale, moderated the talk.

Arthur Ashe, one of the most accomplished tennis players in the twentieth century, blurred the lines between athleticism and politics by using his platform as a Grand Slam-tennis champion to speak out against racism during the Civil Rights era. The first black player selected to the United States Davis Cup team and the only black man ever to win the singles title at Wimbledon, the U.S. Open, and the Australian Open, Ashe changed the role of sports in racial justice in America.

In Arthur Ashe: A Life, published by Simon and Schuster in August 2019, Arsenault documents the upbringing of tennis star Arthur Ashe, who grew up in 1940’s Richmond, Virginia, one of the most segregated cities in the United States at the time. Ashe’s father, Arthur Ashe Sr., was an authoritarian father who worked as the manager of the largest black park in Richmond. There in the park, the Ashe family built their house which happened to be next to four recreational tennis courts—though Ashe never played on the courts.

Ashe’s mother died when he was six years old and he was devastated. “He stopped speaking when his mother died,” Arsenault said. “It wasn’t until a nineteen-year old tennis player from the neighborhood coaxed Arthur out of the house to hit some balls with him that Arthur even touched tennis.”

But tennis did not come naturally to Ashe when he first started. “Arthur was so skinny he had to swing his whole body into every hit on the court. But he practiced every single day. People who knew their family said that he would hit one thousand balls every morning before he went to school. And he did this for years,” Arsenault said.

Ashe went on to win his first national tennis championship at twelve years old. “But this was the ATA [American Tennis Association] tournament—the black tournament. Arthur wasn’t allowed to play in other tournaments,” Sims explained.

“Arthur wrote an autobiography called Days of Grace. And in it he says that the biggest burden in his life was not AIDS, which is how he died, but it was his race,” Arsenault stated.

Sims, who has broken multiple boundaries in the elite sport of tennis himself and was a friend of Ashe’s, explained that in his own tennis journey, “You get used to being the only black kid. The getting-to-know-you part is on the white kids. It was the first time for most of these white kids to be around a black kid.”

Winning one Grand Slam title and championship after another, Ashe started to feel that he needed to pay back to the black community because he missed out on going to Montgomery, Selma, and all those other protests of the Civil Rights movement. “Instead, he was playing a game at fancy tennis courts,” Arsenault said. One ingredient of Ashe’s activism and support for the black community was tennis clinics. Ashe and Sims started a tennis clinic in Richmond where they taught young black children basic tennis skills like holding a racket and hitting the ball.

But his blackness was tokenized in the fame-saturated spirit of tennis. Ashe was the first black athlete to be marketed and to be offered contracts with athletic companies. Ashe hated that journalists always called him “the best black tennis player,” as if he was in a separate category of talented tennis players because of his blackness. When he was young, Arsenault said, Ashe was never allowed to play in Bird Park in Richmond, which was the white park. But when Ashe came back home after having become famous, white people in Richmond said to him, “We loved watching you play in Bird Park when you were young,” ignoring the segregation that permeated his life since he was a boy.

Nevertheless, Ashe used his fame to further social justice movements. He co-founded the National Junior Tennis League (NJTL) as a way to reach young people in inner cities “rather than just hand them a racket for a one-time clinic,” Sims said. “Arthur didn’t want to give tennis to kids. He wanted to give them life skills.”

In 1968, Ashe gave his first public speech in a church in Washington, during which he spoke out against the Vietnam War. When Nelson Mandela was released from prison and came to the United States for the first time, Arthur Ashe was the first person Mandela wanted to meet. Ashe wrote opinion pieces in the New York Times, including an open letter to black parents where he urged, “Take your kids to the library.” Ashe believed in activism through the vehicle of education.

“The last thing [Ashe] did before he died,” Sims said, “was that he wrote on a pad of paper—because at that point he couldn’t talk anymore—and he urged President Clinton to appoint a pro-Civil Rights Justice in the Supreme Court. That was the last thing he ever did. And that shows you what was important to him, even at the end.”

Written by Vy Tran, Yale College Class of 2021.