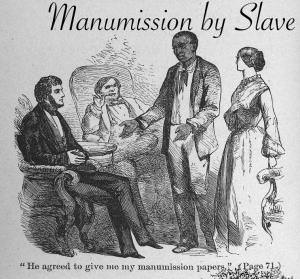

Manumission by Slave

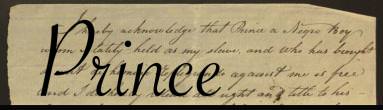

Some of the enslaved had the courage or audacity to use the legal process to secure their liberty. The documents in this collection all feature individuals who were seemingly able to manufacture their own freedoms through negotiations with their owners. Prince, a man enslaved in New York, had the courage to bring a writ of Homine Replegiando, which essentially states that a person is being unlawfully held. His petition was successful, and Prince was manumitted in due course. Similarly, an enslaved woman named Phyllis claimed that she should have been freed when she sold from New Jersey into New York; this plan also gained her present owner’s assent. Finally, a manumitted man named William used his newfound freedom to complain that his former master was continuing to treat him unfairly, citing that he had been free for the last three years.

Some of the enslaved had the courage or audacity to use the legal process to secure their liberty. The documents in this collection all feature individuals who were seemingly able to manufacture their own freedoms through negotiations with their owners. Prince, a man enslaved in New York, had the courage to bring a writ of Homine Replegiando, which essentially states that a person is being unlawfully held. His petition was successful, and Prince was manumitted in due course. Similarly, an enslaved woman named Phyllis claimed that she should have been freed when she sold from New Jersey into New York; this plan also gained her present owner’s assent. Finally, a manumitted man named William used his newfound freedom to complain that his former master was continuing to treat him unfairly, citing that he had been free for the last three years.

In these stories, the power dynamic seemingly rests with the enslaved, who won their freedom according to their own petitions and advocacy. This asks us to question how the legal system could be manipulated to assist an enslaved individual, despite clear codes that established a owner’s rights over the people he enslaved. They also invite us to consider whether these cases are exceptional or not: how else might they have ended?

As you read these documents, consider the following questions.

-

What does the legalistic nature of these manumissions explain to you about the society in which they were living? Should legal activism have led the manumission struggle?

-

What strikes you as most important about the act of gaining freedom by petitioning a court, whether against an abusive former owner, or in favor of one’s own freedom? What impact might it have on people aware of these cases, but not on the side of either party?