Honoring the Dishonorable: Calhoun College at Yale University

Honoring the dishonorable: Calhoun College at Yale University

R. Owen Williams

It seems there are many institutions apologizing for slavery and its aftermath.

In January of 2005 JP Morgan apologized for the financial support two of its predecessors provided nineteenth century slaveholders. In June, Wachovia Bank apologized for organizations it had acquired that owned slaves or accepted slaves as collateral. The Chairman of Wachovia proclaimed, “We can’t make up for the wrongs of slavery…But we can learn from our past, and begin a stronger dialogue about slavery and the experience of African-Americans in our country.” Two weeks later, Congress, which has never expressed regret for slavery, did apologize for blocking anti-lynching laws that might have halted the murder of thousands of blacks from the 1880s to the 1930s. Americans may not be prepared for “a stronger dialogue about slavery and the experience of African-Americans,” but if we are, then the repenting has only just begun.

Of course, nobody wants to be blamed for slavery. The banks were certainly motivated, pressured perhaps, by a Chicago ordinance that required companies wanting to do business with the city to investigate and then disclose whether they ever benefited from slavery. That they were contrite about past profits for the sake of more in the future should not detract, however, from the ultimate integrity of the act.

It used to be that any and all American institutions could ride that old horse, “the country was a different place and we only did what everyone else was doing.” Well, that may just mean that more institutions will indeed have to own up to past harms. Brown University, under the bold leadership of Ruth Simmons—the first African-American president of an Ivy League university and a great-granddaughter of slaves—is presently studying its historic ties to slavery. Yale University may also need to revisit its history.

The Yale and Slavery Report, written by three graduate students in 2001, attacked Yale for having named several of its twelve residential colleges in honor of slaveholders. The report unleashed a temporary furor. Its basic thrust was clear; if an august academic institution such as Yale, lux et veritas, cannot be counted on to recount the truth about the past, who can? Editorials appeared all around the country. Scholars charged that the report was flawed for its lack of historical context. Nevertheless, the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance and Abolition at Yale did host a conference to consider the report’s worthy points. One question in particular arose: why did Yale name a college for the most prominent defender of slavery, John C. Calhoun, in 1933, almost seventy years after the abolition of slavery? That riddle went unsolved. Yet a substantial part of the answer might be found in the timing. The naming took place in the 1930s, precisely when Congress was not passing anti-lynching laws. So the question becomes, should Yale join the line of those apologizing for the past?

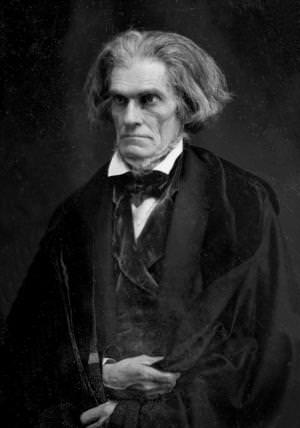

Some will argue that this is a matter for the dustbin of history. What nation, what institution, is not without its compromising memories? Times change; it is best to leave the uncomfortable past in the past. The French scholar Ernest Renan highlighted the trouble historians can stir up. “Forgetting,” he suggested, “is an essential factor in the creation of a nation and that is why progress in historical research is often a threat to nationality.” Why not forget the sins of slavery and those who defended it? Certainly most Yale students pass by Calhoun College without knowing anything about the man for whom it was named. Generally speaking, John C. Calhoun enjoys the same robust oblivion that Americans reserve for other ex-Vice Presidents of the United States. Aside from having been the seventh man to hold that office, Calhoun is most notable for having been a proud slaveholder who tirelessly defended the institution of slavery, as well as the grandfather of Confederate secession. Indeed, he resigned as Vice-President on account of the slaveholding president he served under—Andrew Jackson—was insufficiently proslavery and pro-states’ rights.

Forgetting Slavery, Remembering Calhoun

There are those who will argue that John C. Calhoun was, in fact, a brilliant and accomplished statesman who deserves to be remembered favorably. His autodidactic dedication earned him acceptance to Yale University in 1802, as a third-year upperclassman. The six-foot two-inch farm boy lived a largely solitary existence in New Haven. Indeed, as the only student on campus not to join one of the college’s immensely popular literary societies, Calhoun felt ostracized at Yale. In a letter to his cousin Andrew Pickens, he wrote that there was “a considerable prejudice here against both the southern states and students.” Graduating with high honors among the sixty-six members in his class, Calhoun was selected to present the commencement address, entitled “The Qualifications Necessary for a Statesman,” the delivery of which was prevented by a life-threatening illness.

But nothing could keep Calhoun from becoming a statesman. Apart from his reserved nature, perhaps the defining aspect of Calhoun’s character was aggressive ambition, which earned him all but his most coveted political office. In a career that spanned from 1811 to his death in 1850, Calhoun served in the House of Representatives (1811-1817), as Secretary of War (1817-25), and as Vice-President under John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson (1825-1832), though he resigned from this last position in support of nullification. Apart from a brief stint as Secretary of State (1844-45), Calhoun turned himself over to the work of the United States Senate until his death in 1850. The Presidency, for which he incessantly (though not always openly) campaigned, proved beyond his grasp. So focused was he on that office, that Calhoun went to his grave convinced he had failed for not attaining it.

Calhoun was, without question, among the most intellectually gifted statesmen of the era. Slavery was at the root of his political mission. He told the Senate: “I am a planter—a cotton planter. I am a Southern man and a slaveholder—a kind and a merciful one, I trust—and none the worse for being a slaveholder.” No one was more convinced that slavery was “a good—a great good.” Calhoun’s perception of slavery was predicated upon the inferiority of blacks, a position he frequently articulated. In arguing against allowing free blacks to serve in the Navy, for example, he maintained, “It was wrong to bring those who have to sustain the honor and glory of the country down to the footing of the negro race—to be degraded by being mingled and mixed up with that inferior race.”

Calhoun believed slavery worked to the benefit of all involved. Adamant in his position, he declared, “Come what will, should it cost every drop of blood, and every cent of property, we must defend ourselves.” Calhoun was rarely shy in making his point. And the point he cared most to make was that the South need concede nothing regarding “the peculiar institution” of slavery. Calhoun maintained a profound respect for the Constitution and insisted it protected slavery, thereby avoiding any need for compromise on the subject, which had always been anathema for Calhoun. On February 6, 1837, Calhoun spoke from the Senate floor, saying: “I hold concession and compromise to be fatal. If we concede an inch, concession will follow concession—compromise would follow compromise, until our ranks would be broken.” Of all the senators at the time, none took a harder line in support of slavery than Calhoun. Again, on February 19, 1847, Calhoun expressed his frustration with America’s desire to meld toward the middle, bellowing “Let us be done with compromises.” Compromises were merely words, he insisted, “but the Constitution is stable.” That the Constitution was itself only words, consisting of many compromises, cannot have been lost on Calhoun.

The Senator from South Carolina was a great orator. Of his many spellbinding speeches none was more captivating, or unusual, than his last. On March 4, 1850, fellow Senator James Mason of Virginia read Calhoun’s final speech to the Senate as the gravely ill Calhoun looked on from a nearby lounge chair. As Mason rose to speak for his colleague, Calhoun’s frail condition may have struck gallery spectators as an apt metaphor for southern exhaustion with the attack on slavery. “The South asks for justice, simple justice, and less she ought not to take. She has no compromise to offer, but the constitution; and no concession or surrender to make. She has already surrendered so much that she has little left to surrender.” Within weeks, the uncompromising Calhoun was dead, and Congress was on its way to passing the Compromise of 1850.

Yale, eighty-three years later

In the four years before Yale honored Calhoun, the stock market had just undergone its worst sell-off in history, down ninety per cent! In a letter to the Yale Alumni Club of New York, President James Angell addressed the “world-wide disruptive economic forces” and the difficult situation in which Yale found herself. The correspondence claimed that “Yale now faces a deficit for the current year of $514,000 of which $372,000 is due to shrinkage in returns from interest and dividends.” Incredibly, Yale continued on the trajectory begun around 1900, when the number of students per class was 310. By 1933 most families could ill afford the cost of tuition, yet Yale had 849 freshmen in the class of 1933. As the Depression dragged on, it was primarily the wealthy who went to college at all, let alone an elite private college. Slightly more than seventy-five percent of all Yale students during those years had gone to (northern) private preparatory schools, fifty percent from just eleven institutions. Housing all those students had become the university’s single most pressing problem. President Angell proposed a residential plan modeled after the dormitory quadrangles at Oxford and Cambridge in England. But the university could ill afford it.

Just when housing matters were at their worst, Yale experienced a remarkable stroke of good fortune. Edward Stephen Harkness, class of 1897, son of John D. Rockefeller’s silent partner as co-founder of Standard Oil Company, donated something close to twenty million dollars to his alma mater. The residential plan would become a reality.

Although the Education Policy Committee oversaw all issues associated with the project, Angell immediately appointed several subcommittees to address such matters as personnel, student employment, and housing allocation of students. Of these various committees, Angell believed none was more important that the Committee on Names and Terminology, chaired by the University Secretary. That committee was created to consider what to call the new buildings (Quads, Houses, Colleges, or Halls), titles for senior administrators (Head, Dean, Master, Provost, Principal, President, or Warden), and, most importantly, the actual names for the structures.

On Alumni University Day, February 23, 1931, President Angell announced the initial decisions of the committee, also approved by Yale’s board of trustees known as The Corporation. The residences would henceforth be called “Colleges,” their senior administrators “Masters,” both borrowed from Oxbridge. After having “invited many other persons into conference,” Angell said the committee had “turned its attention to the specific names which might wisely be used for the first of the new colleges.” Angell presented the names of five colleges, which he trusted were “at once euphonious and possessed of a certain intrinsic dignity,” Angell stressed that the committee was “still at work on names for the remaining colleges,” a list of which should be available within months. Recognizing the clear significance of the topic, the President proceeded delicately:

Time does not permit of a complete canvass of the grounds upon which they have rejected, or accepted, certain obvious names. Suffice it to say, that, as far as possible, they have sought to retain appropriate names already in use in connection with the sites upon which will stand any of the new units. They have, in general, attempted to avoid all personal names belonging to the last century—in other words to forgo incursion into the realm of contemporary affairs, with the inevitably acute controversial atmosphere likely to attract to such procedure. Finally, they have tried to exercise due regard to the outstanding figures, or events, in Yale history and in the history of the New Haven Colony.

Concern for this matter was so great that yet another subcommittee, consisting of the Secretary and the Dean, was assigned to address it in isolation.

By April, the Corporation resolved that “the following names be approved as appropriate for the colleges…according as the trustees may select any one: Calhoun College, James Kent College, Jonathan Trumbull College, and Noah Webster College.” James Kent and Noah Webster were among the very most important minds of the nineteenth century. But, by their next meeting, the choice was made. The special “nomenclature committee” had deliberated for more than a year as to who should be honored by the naming of these colleges. It was voted by the Corporation, “The quadrangle which will be built at the corner of Elm and College…shall be named Calhoun College to honor John Caldwell Calhoun, B.A. 1804, L.L.D. 1822, statesman.” During the same meeting, in perhaps a fitting but unnoticed irony, the Yale Corporation also appointed Arnold Whitridge as Calhoun College’s “Master.”

It is worth mentioning that today there are twelve residential colleges at Yale, the two named in 1917 (Branford and Saybrook), five in 1931 (Berkeley, Davenport, Jonathan Edwards, Pierson, and Calhoun), two more having opened in 1935 (Timothy Dwight, and Trumbull), one in 1940 (Silliman), and the final two (Morse and Stiles) in the 1960s. Some colleges were named to honor important figures from the early years in Connecticut (Trumbull) or because they helped give rise to Yale (Berkeley and Davenport), some were named for faculty or administrators (Silliman, Pierson, and Dwight—both Timothy Dwights graduated from Yale, class of 1769 and grandson 1849, and both went on to become Presidents of the University), while other colleges were named to honor significant places in Yale’s history (Branford and Saybrook). Of the total twelve colleges, six are named for graduates of the college.

Of the five colleges named in 1931, however, only two for graduates of Yale. Out of two hundred and thirty years of graduating classes, Yale selected only two names to honor: Jonathan Edwards and John C. Calhoun. University Secretary Carl A. Lohmann reported, “…names had been chosen to represent Yale’s most eminent graduate in the Church and Yale’s most eminent graduate in the field of Civil State.”

It is curious that Yale, as Angell stated, “attempted to avoid all personal names belonging to the last century.” Calhoun was not, in fact, “Yale’s most eminent graduate in the field of Civil State.” William Howard Taft was the 27th President of the United States, from 1909-1913, and the 10th Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, from 1921 until his death in 1930, just months before the naming of Calhoun College. Not only was Taft the first Yale grad to reach either office, he had a long record of service to the university that went well beyond the two years Calhoun spent in New Haven as a student. Taft was a member of the Yale Corporation, or board of trustees, from 1906-1913, and again 1922-1925. Was the current memory of William Howard Taft, the only American to become both President of the United States and Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, more apt to generate controversy than the distant memory of John C. Calhoun, a man whose political career was primarily dedicated to a defense of nullification, sectionalism, and slavery?

We cannot know for sure what the reaction to Taft might have been, but it is clear that the naming of Calhoun College aroused virtually no controversy in 1933, on or off campus. Of the various Yale publications, the Alumni Weekly reported nothing relating to Calhoun College specifically, focusing instead on the larger College Plan. The Harkness Hoot, a campus literary magazine, offered an interesting editorial entitled, “Colleges for Sale,” which pulled no punches: “No, away with University ideals…they have been sold for a cathedral city of movieland magnificence and negroid taste to the wealthiest purchaser of a memorial or two.” [my italics] The Whole Houn Catalogue, an annual brochure introducing Calhoun College to arriving students and one of the few publications to address the memory of Calhoun directly, wrote that the statesman had “influenced the political history of the United States more deeply than any other graduate during Yale’s first two centuries.” The catalogue did not then, and does not still, articulate what that influence had been.

In the Yale Daily News, a rather strange reference can be found. The paper reported that Calhoun College had originally been intended for a location closer to Sterling Library, on the site of what is now Trumbull College. But plans were changed “when the University authorities realized that J. W. Sterling, the donor of the present Trumbull, was a Yankee who had fought in the Civil War, against the principles for which John C. Calhoun had stood so strongly, and that it would be tactless to name his college in honor of a secessionist.”

Off campus, the story was much the same. The New York Herald Tribune covered the naming, on October 15, 1931, in an article entitled “Three New Colleges Named in Yale Residential Plan,” referring to one “in honor of Senator John C. Calhoun, of South Carolina, who was graduated from Yale in 1804.” The next day, The New York Times also carried the story of “New Colleges Named at Yale” that mentioned “Calhoun College in honor of John C. Calhoun, the statesman, Yale 1804.” And yet, neither paper had another word about the man himself. A month later, The New York Times Magazine, writing about designs of the respective colleges, offered the following: “The one college that [architect James Gambell] Rogers did not build is curiously (for Connecticut and New Haven) named after John C. Calhoun, a Yale man, though the great South Carolina nullifier.” Yet, after that, there was no further commentary.

Student reaction to the use of Calhoun’s memory was uniformly muted. In interviews I conducted with the current Class Secretary of each of the first classes to reside in the new Colleges (Class of 1933–as dorms; Classes of 1934, 1935, and 1936–as colleges), none remembered any controversy whatsoever about the name Calhoun. All of these gentlemen were very open in their discussions with me; their remarkably facile recall and conversation completely camouflaged their ninety-plus years. “For most of us,” according to Edwin Clapp, “the moral elements of American history were simply not ingrained, slipped right by us.”

There was, however, at least one voice of objection. At a formal dinner to celebrate the opening of Calhoun College, October 31, 1933, Mr. Leonard Bacon read a poem he had composed for the occasion:

I suppose that I ought

To have bayed at the moon

Singing the praises

of John C. Calhoun.

But I cannot, although

He was virtuous and brave,

And besides my great-grandfather

Would turn in his grave,

If he dreamed of a monument

Raised to renown

Calhoun in this rank

Abolitionist town.

A lonely and half-hearted protest was masked in humor.

One other person would have complained about honoring Calhoun, had he been alive to do so. Benjamin Silliman, for whom one of the other residential colleges was named, tutored Calhoun at Yale. The respected teacher made the following diary entry soon after Calhoun’s death:

John C. Calhoun died at Washington last Sabbath…I have known him from his youth up… If the views of Mr. Calhoun, and of those who think with him, are to prevail, slavery is to be sustained on this great continent forever….While I mourn for Mr. Calhoun as a friend, I regard the political course of his later years as disastrous to his country and not honorable to his memory, although I believe he had persuaded himself that it was right, and that he acted from patriotic motives.

What enabled Yale to overlook the “political course” of Calhoun’s later years, especially given that Silliman absolutely could not? Did Yale somehow hope to benefit from an association with Calhoun’s ultra-southern doctrines?

Perhaps the University was reaching out to southern alumni as potential donors at a time of financial stress. Records show, however, that southerners constituted a mere 5.1% of all living graduates. Furthermore, while Yale was experiencing financial difficulties, like all institutions public and private, its investment income was actually down only 8.5%. It is also possible that Yale wanted to increase enrollment of southern students, particularly since that number had dropped from a pre-Civil War high of 13% to only 2% immediately after the War; the post-Civil War high of 6% occurred in 1929, just prior to naming Calhoun College. Yale certainly cared about the geographic distribution of their student body, as demonstrated by both specific data within the Department of Personnel Study of 1932 and the Yale Directory, which in 1926 began keeping records by students’ home states. But, if Yale named Calhoun College in hopes of attracting southern students, their efforts were for naught. The percentage of southerners did not even get to 1929 levels again until 1946, and antebellum rates proved completely unattainable.

It might be possible to explain the naming of Calhoun College as part of an economic rebuilding of America, or as a bridge to the promise of a New South. The future of the South was very much on people’s minds, and there were those, such as the literary group dubbed the Fugitives, a group of southern poets and novelists (e.g. John Ransom, Allen Tate, and Robert Penn Warren) who advocated the southern agrarian way of life and were very influential in the 1920s. They felt that “younger southerners, who are being converted frequently to the industrial gospel, must come back to the support of the Southern tradition.”

A different kind of conversion was taking place in New Haven. The Yale Corporation, established in 1701 by Connecticut state legislation, named ten ministers as the original trustees, and provided for them to select their “successors.” In 1871, another Act of General Assembly of Connecticut stated that six graduates would be elected to six-year terms, and that the Governor and Lt.Governor of Connecticut would also serve in the corporation. While the Corporation had traditionally been exclusively composed of ordained ministers, only admitting its first non-minister in 1905, by 1930 all but three of ten permanent members were leaders of industrial society, making the board something of a proxy for corporate America. And Calhoun’s political theory, after all, was predicated upon the notion of free trade, which he regarded as “emphatically the cause of civilization and peace.” But, here again, if the trustees hoped to lean on Calhoun as an economic inspiration toward a new South, they never made mention of his southernisms.

In fact, the story becomes muddier upon considering Yale’s subsequent perceptions of both Calhoun and slavery. In 1914, Anson Phelps Stokes wrote a two-volume Memorials of Eminent Yale Men that offered a ten-page biographical sketch of Calhoun. It opined, “Being an ardent Southerner he was naturally also a defender of slavery.” Of course, as subsequent historians have demonstrated, it was not “naturally” the case that southerners defended slavery. In the 1920s, another Yale publication celebrated Calhoun as one of Yale’s forty-three “worthies,” past graduates whose names were carved above the entry ways at Memorial Quadrangle and whose biographies can be found in The Memorial Quadrangle: A Book about Yale. The author, in what was the University’s official biography of those important historical figures, posed the following query: “What does it matter now whether Calhoun was right or wrong? We can see the honest convictions that lay at the bottom of his thinking, and that is all that need concern us.” And a bit further on, “the defeat of everything he stood for cannot obscure his gigantic and impressive figure.” If the moral as well as practical defeat of everything one stands for does not bring a person down in size, then what does?

Yale University Press and Yale scholars contributed to a rewriting of history that rehabilitated the antebellum South. Among American historians, none were more influential than Ulrich B. Phillips, son of a planter, grandson of a slaveowner, and protégée of Old South apologist William Dunning. Phillips taught at Yale. His book American Negro Slavery (1918) shaped America’s sense of slavery for more than a generation. Eugene Genovese offered this concise assessment: “Let there be no mistake about it; Phillips was a racist.” Phillips presented a southern perspective, characterizing slaves as innately inferior and slavery as a kind and humane institution. Thanks to such arguments, the early decades of the twentieth century, more than any period in American history, were dominated by a southern racial dogma that presupposed black inferiority.

So, the issue seems to have been not what Yale knew about Calhoun and slavery, but what the Yale Corporation, like the rest of America, chose to forget. Yale either knew all along that resistance to the memory of Calhoun would be negligible, or they too never thought of it.

It was not until much later that Yale students (mostly African American students, to be precise) resisted “Calhoun” as the name for one of the residential colleges and tried to get the name changed. In 1989, Christopher Rabb, Class of 1992, confronted then Master of Calhoun, Ramsey MacMullen, and demanded the removal of a certain stain-glassed window. Rabb recently told me he now regrets the removal of this historically significant evidence, which he said contained “a very demeaning image of a kneeling slave in tatters, paying homage to Secretary of War Calhoun.” At the back wall of the common room in Calhoun College, there was a plaque containing a manifesto written and read by Rabb at college commencement exercises in May 1992. That manifesto, addressing the concerns of several African American students in the classes of ’92 and ’93, criticized Yale for honoring a white supremacist. For reasons unknown to the current Master, that plaque is now nowhere to be found.

The Lost Cause

Calhoun College was named on the heels of the worst time in American race relations. In fact, while the thirteenth amendment to the U.S. Constitution eliminated slavery in 1865, it simultaneously unleashed a different and arguably more corrosive form of racism from what had previously existed. Many Americans quickly accepted a post-Civil War theory of causation, commonly referred to as the Lost Cause, which posited secession and the Confederacy as the fight for states’ rights. Initially an attempt to explain Southern defeat, this hypothesis evolved through several decades and permutations to eventually erase slavery as a cause of the Civil War. The Confederacy grew increasingly romanticized and the honor of the Old South restored. Through it all, what was really “lost” was the reality of slavery.

America reached the nadir of the Jim Crow era in the 1890s with few individuals or institutions untouched. By the turn of the twentieth century, the Lost Cause had given rise to both a celebration of the Confederacy and a reinvigorated white supremacy. What is most surprising about that theory, however, is the extent to which it took hold in the North as well as in the South. Even as the last Confederate soldiers passed away and Civil War reunions dwindled, the Lost Cause lived on.

Popular literature, minstrel acts, and vaudeville shows represent blacks as buffoons, and films like Birth of a Nation incited whites to vigilantism. Membership of the Ku Klux Klan soared, from five thousand in 1911 to five million in 1925, even though membership subsequently dropped. A burgeoning anti-immigration movement, as exemplified by books such as Lothrop Stoddard’s The Rising Tide of Color Against White World-Supremacy, was rooted in race hatred. Lynching mobs exterminated thousands of blacks, starting in the 1880s and not slowing until the early 1930s. As the historian Leon Litwack has pointed out, “not even a liberal president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, was willing to endanger his southern white support by endorsing [anti-lynching] legislation.” By 1928, the American Mercury could report on a Confederate reunion and ponder whether a better era had long since passed: “maybe, after all, they should have won the War…It would have given us a technique of leisure, a calmer estimate of life’s values.”

As the Lost Cause became common parlance, students at Yale began to develop a local culture around their new colleges, giving each a nickname. Pierson College’s white-painted courtyard “reminiscent of slave quarters on a Carolina plantation, suggested ‘Slaves’.” A nickname of “slaves” posed little threat for young men of privilege. White supremacy solidified, at Yale and throughout America, as the nation increasingly forgot the realities of slavery.

The Yale Corporation presumably wanted to distinguish their institution for having graduated a man who attained the nation’s executive branch, despite whatever he might have done thereafter. Since the 1930s, as Yale proudly boasts, the university has had several graduates become President: Gerald Ford (Yale Law), Bill Clinton (Yale Law), and both George Bush Sr. (Yale College) and George W. Bush (Yale College). But in 1931 the university needed a name from its past that would not stir unfavorable memories yet provided an opportunity to emphasize Yale’s political clout and public service. That must have been their purpose. Jim Crow racism, rehabilitative history, and the preoccupation with hierarchical stature all enabled Yale to overlook Calhoun’s “peculiar institution.” The era of the Lost Cause made it possible to neglect the fact that Calhoun, unlike the various slaveholding Presidents and Vice-Presidents whose support for slavery was either tepid or ambiguous, had actively and passionately defended the institution.

Apologizing, 140 Years After Slavery

Why is any of this important today? What is the connection between slavery in the 19th century and racism in the 20th, or Yale in the 21st? America has never officially apologized for, nor adequately examined the extent to which racism grew out of, slavery. Every year since 1989, Michigan Representative John Conyers has proposed a bill, HR 40, to study the effects of slavery. That bill has never even reached the floor for debate. The time for honesty is long overdue. If the truth about the past is to be known, courageous leadership is required. As was suggested in the Yale and Slavery Report, “it is incumbent upon Yale to be a vanguard force, to serve as an example.”

But to rewrite history yet again, by erasing the name Calhoun at Yale, would not do. There is a better way. Amend the name of Calhoun College in a manner that reflects the past while simultaneously holding out promise for the future. Consider this: Calhoun/Bouchet College. Edward Alexander Bouchet, born September 15, 1852, was the first black American to achieve any number of milestones: first black undergraduate at Yale, in 1874, 6th in his class of 124; first of all students in the class of 1870 at Hopkins School; first black nominated to Phi Beta Kappa, elected in 1884 (the first elected was G. W. Henderson in 1877); and, perhaps most importantly, in 1876, the first black to earn a Ph.D. at any American university (the sixth person ever in physics). That honor, first black Ph.D., is often incorrectly attributed to W.E.B. Du Bois, who took his degree at Harvard in 1895, almost twenty years after Bouchet. Due to racism, Bouchet was unable to earn a teaching position at a college or university, so he taught at the Institute for Colored Youth in Philadelphia for twenty-six years before his death in 1918.

Assuming Yale seeks to honor academic excellence, as well as elevate its own historical significance, who better to honor than Edward Alexander Bouchet. Partnering him with John C. Calhoun tells a more complete story, one of greater integrity and justice. The time has indeed come to apologize for slavery and racism. The time has come for Calhoun/Bouchet College.

(The writer of this article is currently a Ph.D. candidate in history at Yale University, specializing in slavery and Reconstruction. He was previously an investment banker for twenty-four years—at Salomon Brothers, Goldman Sachs, and Wachovia—and managed the business that later prompted Wachovia’s apology for slavery.)