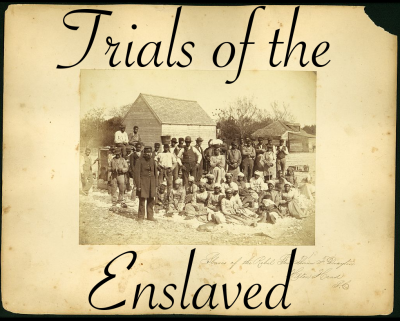

Trials of the Enslaved

Until Chief Justice Roger Taney’s notorious Dred Scott decision declared in 1857 that blacks had “no rights which the white man was bound to respect,” the legal status and privileges given to the enslaved—as well as to free blacks—was unique to each state. In some cases these individual state laws were cause for national controversy, yet much more often blacks found themselves on the margins of local laws, given certain rights and statuses in some cases and deprived of them in others.

The following four incidents—from Northwest Georgia in 1786 and 1792, Southeastern Virginia in 1818, and Western Virginia in 1854—demonstrate differences in the legal proceedings and liabilities that faced several enslaved people who entered into Southern legal proceedings in life or in death.

“Trials of the Enslaved” is designed to provide inquiry-based opportunities for students to examine slavery from a personal perspective. These documents challenge students to examine one of the most problematic aspects of slavery, the inherent contradiction of enslaved peoples being treated as both human beings and property. The “value” that slave owners imparted to the enslaved rested in the very human qualities they possessed. Slaves could work, talk, learn, ask questions, improve, and do a myriad of other things that a plow or horse simply could not do. And all of these traits led directly to the slave holder knowing, at some deep and obvious level, that the enslaved were people and not objects. The ensuing difficulty of reconciling what at some level every slave-owning society knew to be true. In these documents, students can begin to grapple with these challenges themselves.

Teacher Notes:

“Trials of the Enslaved” lends itself well to a general introduction followed by breaking up the class into four groups. Some possible compelling and supporting questions to guide the lesson include:

- How did the fact that the enslaved were human beings complicate legal proceedings in the South that also treated them as property?

- In what specific ways does the law treat the enslaved as people and in what ways as property?

- What circumstances would make slave owners emphasize one aspect over the other?

A good starting point might be a reminder activity about the legal status of slavery in the United States from 1786 until 1854, beginning with the Constitution. The dual nature of the enslaved as both human beings and property is clear from the Constitution’s describing them as “other persons,” “such persons,” or as a “person held to Service or Labour.”

Your students might also reflect on South Carolina General Charles Pinckney’s support of the Constitution because of the protection it gave to the institution of slavery: “We have a security that the general government can never emancipate them, for not such authority is granted.”